During the War

The Merchant Marine

-

Technically outside of the military, the Merchant Marine was much more lenient in employing African Americans. Black mariners were allowed to sign on to any billet for which they were qualified, though some shipping companies employed by the US government still required that crews be segregated by race.

In 1942, Captain Hugh Mulzac, commander of the SS Booker T. Washington, became the first African American ever to receive a master’s license at the helm of the first US merchant vessel named for a black man. Courtesy of the Department of Transportation.

In 1942, Captain Hugh Mulzac, commander of the SS Booker T. Washington, became the first African American ever to receive a master’s license at the helm of the first US merchant vessel named for a black man. Courtesy of the Department of Transportation. In 1942, Captain Hugh Mulzac, commander of the SS Booker T. Washington, became the first African American ever to receive a master’s license at the helm of the first US merchant vessel named for a black man. Courtesy of the Department of Transportation.

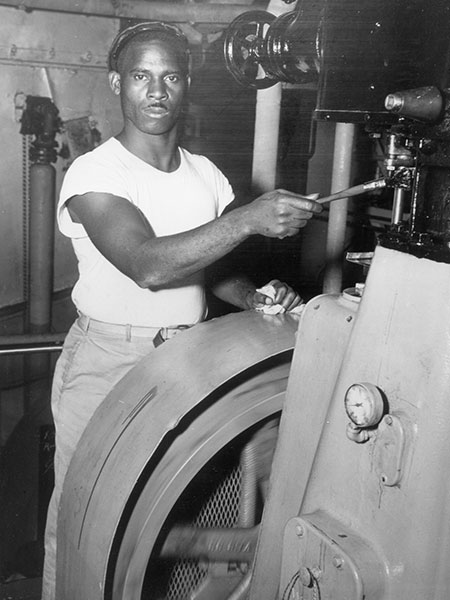

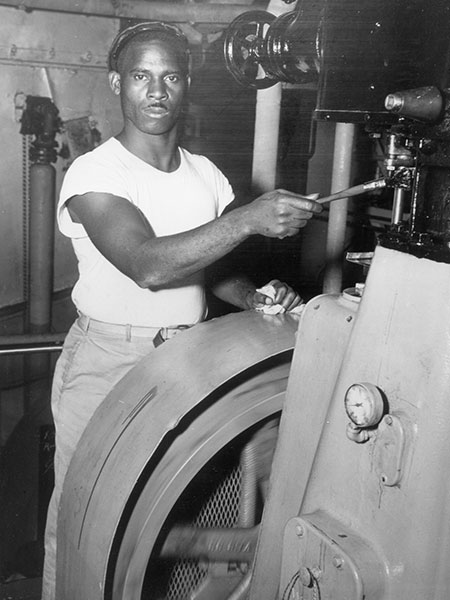

In 1942, Captain Hugh Mulzac, commander of the SS Booker T. Washington, became the first African American ever to receive a master’s license at the helm of the first US merchant vessel named for a black man. Courtesy of the Department of Transportation. Arnold R. Fesser served in the Merchant Marine as an oiler. He had worked as a mariner for 13 years before serving during the war. National Archives, 357-G-203-4690.

Arnold R. Fesser served in the Merchant Marine as an oiler. He had worked as a mariner for 13 years before serving during the war. National Archives, 357-G-203-4690. Arnold R. Fesser served in the Merchant Marine as an oiler. He had worked as a mariner for 13 years before serving during the war. National Archives, 357-G-203-4690.

Arnold R. Fesser served in the Merchant Marine as an oiler. He had worked as a mariner for 13 years before serving during the war. National Archives, 357-G-203-4690. -

The Merchant Marine Academy began graduating black officers in 1944 with Joseph B. Williams, Sr., who sailed aboard the Washington with Captain Mulzac. By war’s end, 17 Liberty ships had been named for African Americans. Over 24,000 black men went to sea with the Merchant Marine, nearly 10 percent of the service’s strength.

-

Merchant Marine vessels with mixed-race crews were known as “checkerboards.” Here, mariners from the Liberty ship SS Booker T. Washington play with their mascot, Booker. National Archives, 111-SC-180663.

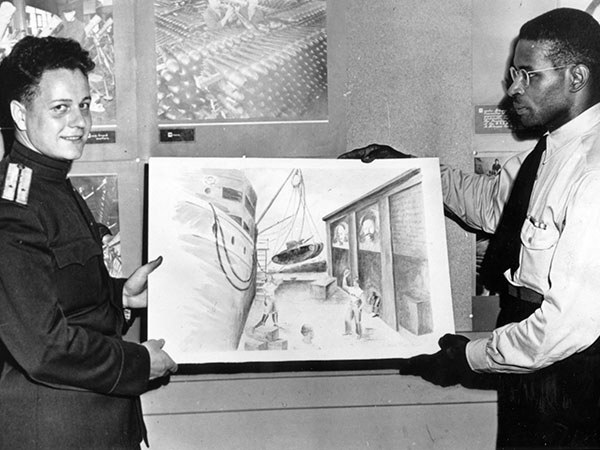

Merchant Marine vessels with mixed-race crews were known as “checkerboards.” Here, mariners from the Liberty ship SS Booker T. Washington play with their mascot, Booker. National Archives, 111-SC-180663. Merchant seaman and artist George Wright presents a painting depicting cooperation between merchant mariners and Soviet dockworkers to a Soviet officer in August 1944. National Archives, 208-N-31563.

Merchant seaman and artist George Wright presents a painting depicting cooperation between merchant mariners and Soviet dockworkers to a Soviet officer in August 1944. National Archives, 208-N-31563.